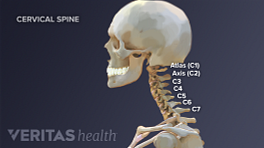

When the cervical disease encompasses more than just the disc space, the spine surgeon may recommend removal of the vertebral body as well as the disc spaces at either end to completely decompress the cervical canal.

This procedure, a cervical corpectomy, is often done for multi-level cervical stenosis with spinal cord compression caused by bone spur (osteophytes) growth.

See Cervical Osteophytes: Symptoms and Diagnosis

What Occurs in Anterior Cervical Corpectomy Surgery?

The general procedure for anterior cervical corpectomy surgery is as follows:

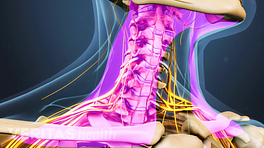

- The approach is similar to a discectomy (anterior approach), although a larger and more vertical incision in the neck will often be used to allow more extensive exposure.

- The spine surgeon then performs a discectomy at either end of the vertebral body that will be removed (e.g. C4-C5 and C5-C6 to remove the C5 vertebral body). More than one vertebral body may be removed.

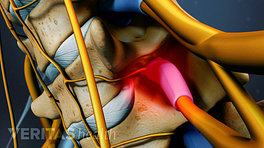

- The posterior longitudinal ligament is often removed to allow access to the cervical canal and to ensure complete removal of the pressure on the spinal cord and/or nerve roots.

- The defect must then be reconstructed with an appropriate fusion technique.

Anterior Cervical Corpectomy Risks and Complications

Technically, a corpectomy is a more difficult spine surgery to perform. Similar to a discectomy, the risks and possible complications of this surgery for cervical spinal stenosis include:

- Nerve root damage

- Damage to the spinal cord

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Graft dislodgment

- Damage to the trachea/esophagus

- Continued pain.

However, a corpectomy is a more extensive procedure than a discectomy, so the risks are statistically greater, especially with respect to neurologic issues, bone grafting and bleeding.

The risk that spine surgeons worry about the most is compromise of the spinal cord that can lead to complete or partial quadriplegia. Bear in mind that corpectomy surgeries are most often undertaken in circumstances of significant spinal cord problems, which place the cord at greater risk for problems during surgery, independent of the skill and finesse with which the procedure is performed.

In This Article:

To help manage this risk, the spinal cord function is often monitored during surgery by Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEP). SSEPs generate a small electrical impulse in the arms/legs, measure the corresponding response in the brain, and record the length of time it takes the signal to get to the brain. Any marked slowing in the length of time may indicate compromise of the spinal cord.

There is also a slight risk that while removing the vertebral body, the vertebral artery that runs on the side of the spine may be injured, which can lead to a cerebrovascular accident (stroke) and/or life-threatening bleeding. This particular risk will be more significant in certain instances of tumor removal or vertebral infections.

Strut Graft to Achieve a Spinal Fusion

After a corpectomy has been performed, the surgeon needs to mechanically reconstruct the defect created and to provide the long-term stability of the spine with a spine fusion. A strut graft is a piece of bone (1-2 inches) that is inserted into the trough created by the corpectomy(ies) and that supports the anterior vertebral column. The graft may be either an allograft or an autograft, and is usually then followed by anterior instrumentation to help hold the construct together.

Alternatively, ‘cages’ made of titanium or other synthetic materials may be employed as an alternative to strut grafts. Such cages are used in combination with morsels of bone graft, which are commonly the ‘local’ autograft bone obtained from the patient as the vertebrae are removed. If multiple levels are fused, a supplemental poster fusion and instrumentation may be recommended to help stabilize the spine.